AI Sitting Posture Detection with NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano: Continuous Learning and Improvement (Part 3)

Learn how to implement continuous model improvement for YOLO-based posture detection on the Jetson Orin Nano—from logging predictions to automated retraining.

Learn how to implement continuous learning in a YOLO-based posture detection app on Jetson Orin Nano, including automated data collection, human-in-the-loop labeling, and scheduled model fine-tuning.

This post continues my journey with the Jetson and also AI workloads. During this journey, I am taking you along my learning experience about running AI workloads, and just "getting into AI" in general. I will be sharing my experiences, learnings, challenges I encountered, and everything in between. In the last post I added a web UI and alerting to my Jetson Posture Monitor app. You can read about it here:

This post is the third in a series of posts where I work on an AI application looking at my posture while sitting, alerting me when I start to slouch or sit with bad posture. The focus for this third post will be on implementing continuous learning in the app, improving the YOLO classification model over time by continuously collecting new data and using that to fine-tune the model continuously.

Project introduction and goal

I've been struggling with my sitting posture since forever now. Whenever I am working at a desk - of which I do a lot - I just cannot sit straight with good posture. I keep shifting around, sitting cross legged or even sitting uneven, leaning and putting strain on one side of my body. I also slide down my chair a lot, "shrimping" (slouching) in the chair.

While shifting around while sitting isn't bad per se, I do think that these ways in which I am sitting aren't healthy either. I'd much rather sit straight with good form while sitting, and then switch it up with my standing desk throughout the day.

That's where the first project I want to do with the Jetson comes in: Detect whenever I am sitting in a "bad" position and send alerts whenever I do.

As of now, I have planned four parts for this project:

- Part 1: Model training and preparation

- Part 2: Web UI and alerting

- Part 3: Implementing a continuous learning cycle with human feedback to improve the model even further over time (this post!)

- Part 4: Increasing efficiency by using a lightweight person detection model as a pre-filter, only running the posture detection model when a person is present

Every blog post about this project can be found here:

All code for this project and mentioned in the following blog post can be found in the GitHub repo:

https://github.com/denishartl/jetson-posture-monitor

My last post was about part 2 of this project, adding a web UI and alerting through a MacOS app.

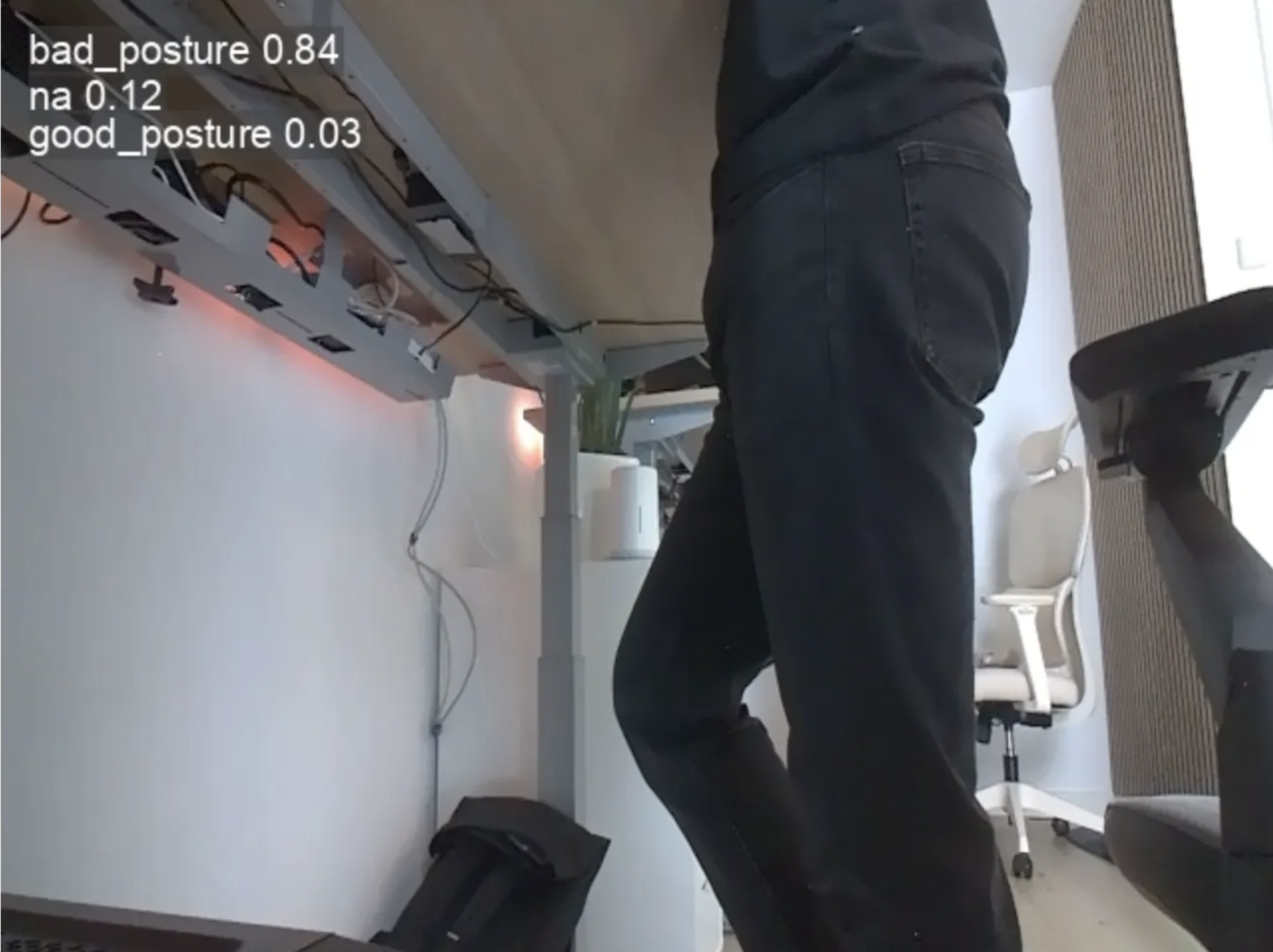

This third part will be about implementing continuous learning into the app. By collecting and classifying new training images and using them to continually train the YOLO classification model I hope to improve the model's performance further with time. As of now, there are many cases where to model is inaccurate. Sometimes there are edge cases where the model struggles, but sometimes it also is just flat out wrong, for example detecting me standing at the desk as "bad posture".

Cases like this, and also different clothing, lighting conditions, etc. all are cases where I hope to improve model performance by allowing it to continually learn on new training data.

Logging

I had the app running for a while on the Jetson, but from time to time it would just stop working. The web server would respond, but no new images and status messages were pushed via websocket, and (I assume) inference was not running at all.

Unfortunately I had no idea what was going an, as any output or log from within the inference loop would not find its way to the systemd logs of the system service I previously created.

To fix that, I decided to add some basic logging to the app, specifically to the inference loop.

First I initialized the logger within main.py.

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logging.basicConfig(

level=logging.INFO,

format='%(asctime)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s'

)Then I added some basic logging to get the stack trace within the inference loop in inference.py whenever an error occurs.

except Exception as ex:

logger.exception(str(ex))I also updated the try/except structure and while loop for recover from failures.

class InferenceLoop:

...

async def run(self):

...

try: # First loop to move cap.release to the finally statement and make sure camera gets released

while True:

try: # Second loop to retry inference whenever it fails

...

except Exception as ex:

logger.exception(str(ex))

finally:

await asyncio.sleep(0.1)

finally:

cap.release()Now I can see logs from within the inference loop correctly in the systemd messages and see whenever an error causes the inference loop to fail.

Gathering training data for continuous learning

The first step towards implementing continuous improvement is to collect more data. For this I re-purposed some logic from my initial data collection script I used, but packaged it into the jetson-posture-monitor service running on the Jetson. You can read more about initial model training and data collection for this project in part 1 of my series.

There was one issue I had to solve before even starting to capture images: Camera Access. Handling of the camera stream was part of the inference loop I implemented in part 2 of this project. That meant that the inference loop process exclusively handled the camera stream, making it impossible for other processes to also access the camera stream. There can only be one stream of the camera, or at least I did not manage to open multiple streams at the same time.

This was an issue, because I also needed access to the camera to be able to capture more training images. I could've just added the code directly into the inference loop, but I wanted to keep inference and image capture separate from each other. And it was an interesting challenge to thing through and implement.

My idea was to move camera management and the camera feed to a dedicated instance (I called it controller). The controller will open and close the camera feed on application start and stop, and also continuously get current images from the camera feed. The current image gets written to the application state in state.py, which I also introduced in part 2 of the series. This way the current image of the camera feed is always available wherever needed throughout the application.

# Buffer current frame for use throughout the application

self.current_camera_frame = NoneProperty to track current camera frame in state.py

The controller then also starts two background tasks for the image capture and for the inference loop.

import asyncio

import cv2

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

def gstreamer_pipeline(

capture_width=640,

capture_height=480,

framerate=30,

flip_method=2,

):

return (

"nvarguscamerasrc ! "

"video/x-raw(memory:NVMM), "

"width=(int)%d, height=(int)%d, "

"format=(string)NV12, framerate=(fraction)%d/1 ! "

"nvvidconv flip-method=%d ! "

"video/x-raw, width=(int)%d, height=(int)%d, format=(string)BGRx ! "

"videoconvert ! "

"video/x-raw, format=(string)BGR ! appsink drop=true max-buffers=1"

% (capture_width, capture_height, framerate, flip_method, capture_width, capture_height)

)

class Controller():

def __init__(self, state):

self.state = state

async def run(self):

try:

# Start camera feed

cap = cv2.VideoCapture(gstreamer_pipeline(), cv2.CAP_GSTREAMER)

# Warm-up: discard first ~30 frames to let auto-exposure stabilize

for _ in range(30):

cap.read()

# Start background tasks for inference and image capture

posture_monitor_task = asyncio.create_task(self.state.posture_monitor_inference_loop.run())

image_capture_task = asyncio.create_task(self.state.image_capture_loop.run())

try:

while True:

# Continuously capture camera image and save to state to use throughout application

ret, self.state.current_camera_frame = cap.read()

if not ret:

break

# Allow kernel to process other instructions

await asyncio.sleep(0.1)

finally:

# Close camera feed gracefully

cap.release()

# Stop tasks for image capture and inference

posture_monitor_task.cancel()

image_capture_task.cancel()

except Exception as ex:

logging.exception(str(ex))controller.py

I largely reused the existing logic for image capture. This means there is a YOLO object detection model (yolo11m.pt) running on the camera stream, monitoring if there is any person in the camera frame. You can read more about this logic in my blog post about implementing data capture.

from ultralytics import YOLO

import logging

import cv2

import datetime

import time

import asyncio

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

class ImageSaver():

def __init__(self, state):

self.state = state

self.model = YOLO(f"{self.state.model_path}/yolo11m.pt") # Load model for person detection

async def run(self):

last_save = 0

ft = "%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S%z" # DateTime format for output

try:

while True:

if self.state.training_in_progress == False:

person_count = 0

results = self.model(self.state.current_camera_frame.copy(), verbose=False)

# Get amount of persons in current frame

for r in results:

boxes = r.boxes

for box in boxes:

cls = int(box.cls[0])

conf = float(box.conf[0])

# Only keep class 'person' (COCO class id 0)

if cls == 0 and conf > 0.5:

person_count += 1

# Set interval depending on if person is present

interval = 180 if person_count > 0 else 3600

now = time.time()

if now - last_save >= interval:

# Save the image if interval has passed since last image

t = datetime.datetime.now().strftime(ft)

cv2.imwrite(f'{self.state.dataset_path}/uncategorized/image-{t}.jpg', self.state.current_camera_frame)

logger.info(f"Saved image at {t}, persons detected: {person_count}")

last_save = now

await asyncio.sleep(0.1)

except Exception as ex:

logger.exception(str(ex))If there is a person, a new image gets captures every 3 minutes. If not, a image gets captured once per hour. I did this to get more images of me actually being present at my desk in as many positions as possible, but also to get some data of me being not present. This whole loop continuously runs in the background while posture detection is also running, collecting more and more training images to be used for model improvement.

💡 One idea to improve this could be to convert the model to TensorRT format. As I previously discovered, converting the model can have an significant impact on inference performance on Jetson, reducing overall hardware load.

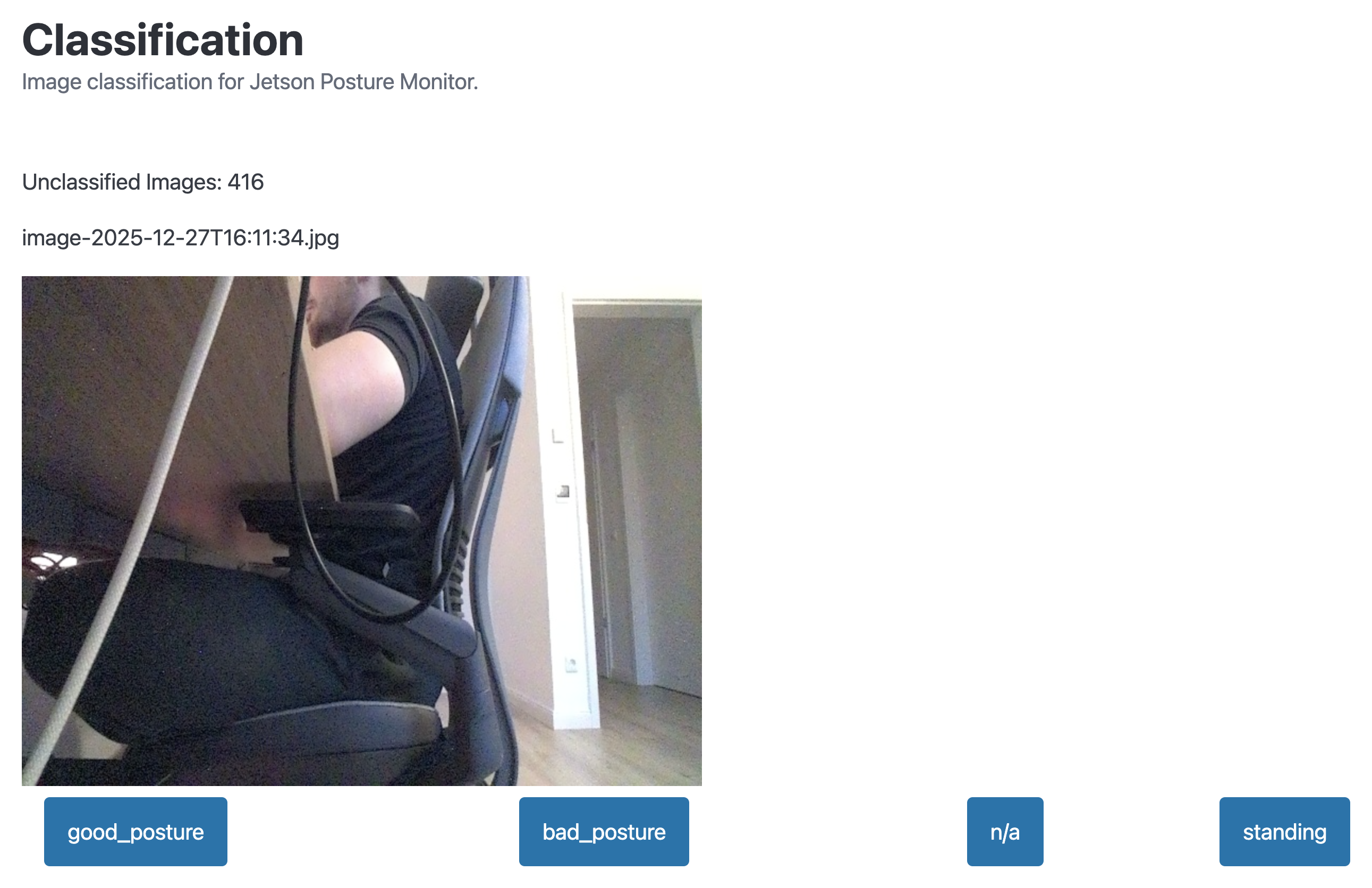

Classifying training data

The newly captured training images need to be labeled/assigned to their class before they can be used for training. This is the "human in the loop" part. A human (aka. me) labels all newly created training images before they are being fed into the model.

I expanded the web UI with a new view which shows a preview of the image about to be classified, and four simple buttons to quickly choose the class to which the image belongs. By using some Javascript magic, the web UI works in a simple loop:

- Fetch image via API

- Wait for user input

- Report back user input via API

- Fetch new image

- Repeat until no images left

The web UI for image classification looks like this:

To serve this web page, I added another route to FastAPI in main.py, serving the HTML template.

@app.get("/classification")

async def classification():

return FileResponse("static/classification.html")FastAPI route for classification web UI

I also added two API paths used to get the image data and to process the user input.

@app.get("/api/classification/next")

async def next_image_for_classification():

return get_next_image_for_classification()

@app.post("/api/classification/classify")

async def classify_image_endpoint(image_classification: Image_Classification):

classify_image(image_classification)

return {}FastAPI paths for classification

These map to their respective functions within classification.py. Function get_next_image_for_classification simply returns the oldest uncategorized image from the capture directory. Function classify_image then moves the image to the respective folder, depending on which class was chosen by the user. A random 80/20 split is applied to distribute images between training and validation datasets.

import base64

import os

import random

# Gets the next image which should be classified

def get_next_image_for_classification(state):

list_of_files = os.listdir(f'{state.dataset_path}/uncategorized')

full_path = [f"{state.dataset_path}/uncategorized/{x}" for x in list_of_files]

oldest_file = min(full_path, key=os.path.getctime)

with open(oldest_file, "rb") as image_file:

image_as_b64 = base64.b64encode(image_file.read())

return {

"number_of_unclassified_images": len(list_of_files),

"img_name": oldest_file.split("/")[-1],

"img": image_as_b64.decode("ascii")

}

def classify_image(image_classification, state):

# Get a random number for split between train and val

random_num = random.random()

# Set train/val and class folders

new_folder = "train" if random_num <= 0.8 else "val" # randomly split images between train and val

user_input_folder = "good_posture" if image_classification.selected_class == 1 else "bad_posture" if image_classification.selected_class == 2 else "na" if image_classification.selected_class == 3 else "standing"

# Construct new file path

new_file_path = f"{state.dataset_path}/{new_folder}/{user_input_folder}/{image_classification.img_name}"

# Move file

os.rename(f"{state.dataset_path}/uncategorized/{image_classification.img_name}", new_file_path)Python logic for classification API endpoints in classification.py

Implementing continuous model training

When starting to implement the continuous learning loop into my Jetson Posture Monitor app, I had no idea how to implement model training at all. Should I train a model from scratch every time? Would some simple fine-tuning be sufficient?

To find out, I explored the topic a bit and found out, that fine-tuning while freezing lower layers in the model actually gave me the best results. Combined with the much lower memory usage for training, this was very good news. Memory is VERY limited on the Jetson, so memory savings is always good news. Here is a more detailed report on my findings regarding training:

On a high level, these are the steps happening during model training:

- Prepare training dataset

- Stop the inference and image capture loop

- Train the model

- Convert the model to TensorRT

- Remove training dataset

- Start the inference and image capture loop

The following sections will get into more detail for each step.

Persisting application settings

When I started to implement the learning loop, I quickly stumbled upon the first issue: How should I track the last time the model was trained? As of now, all settings within the app are not persistent throughout app restarts. To fix this, I added some logic to the AppState in state.py to automatically save and load all relevant settings to a simple config.json JSON file.

First I added functions for loading and saving settings from the JSON file. The use of config_file_content.get() is especially useful here, as it allows for graceful handling these two cases:

- There is no

config.jsonat all - One specific setting is missing from

config.json

In both cases, config_file_content.get() returns the defined default value, mitigating issues where values are not (yet) defined.

def _load_config(self):

if CONFIG_PATH.exists():

config_file_content = json.loads(CONFIG_PATH.read_text())

else:

config_file_content = {}

self._interval = config_file_content.get("interval", 3)

self._alerting_enabled = config_file_content.get("alerting_enabled", True)

self._alerting_cooldown_seconds = config_file_content.get("alerting_cooldown_seconds", 60)

self._alerting_threshold_seconds = config_file_content.get("alerting_threshold_seconds", 10)

self._last_training_timestamp = datetime.strptime(config_file_content.get("last_training_timestamp", "19700101000000"), "%Y%m%d%H%M%S")

self._dataset_path = config_file_content.get("dataset_path", '/home/hartlden/private/jetson-posture-monitor/dataset/')

self._model_path = config_file_content.get("model_path", '/home/hartlden/private/jetson-posture-monitor/models/')

self._save_config()

def _save_config(self):

settings_to_save = {

"interval": self._interval,

"alerting_enabled": self._alerting_enabled,

"alerting_cooldown_seconds": self._alerting_cooldown_seconds,

"alerting_threshold_seconds": self._alerting_threshold_seconds,

"last_training_timestamp": datetime.strftime(self._last_training_timestamp, "%Y%m%d%H%M%S"),

"dataset_path": self._dataset_path,

"model_path": self._model_path,

}

CONFIG_PATH.write_text(json.dumps(settings_to_save, indent=2))Python functions to load and save config in state.py

The use of private properties here is also notable. Every property starts with an _ (e.g. _alerting_enabled). My thought behind that is that I always want to trigger _save_config() whenever a property in AppState is set anywhere throughout the application. Using private properties then allows the use of @property decorators for functions, allowing functions to be exposed as properties. This essentially allows for the easy addition of getter- and setter-methods for each property.

@property

def alerting_enabled(self):

return self._alerting_enabled

@alerting_enabled.setter

def alerting_enabled(self, value):

self._alerting_enabled = value

self._save_config()Getter- and setter-method example for property alerting_enabled

The setter-method always includes self._save_config(). This makes sure that changes to any property within AppState automatically get persisted to config.json as soon as they are changed. I implemented this logic for all AppState properties where persistence across app restarts is useful or important.

Dataset preparation

Now that the application has can "remember" when the last model training run happened, actual preparation steps for implementing model training could start. The first step was to create a dataset with all new images the model has not been trained on before.

The function below creates a temporary dataset by comparing the creation timestamp of the training images to the last training timestamp. Images added after the last training run get copied into the temporary dataset to prepare them for the next training run. I use image names here to determine the image creation date rather ran metadata, as metadata can change when images get copied around.

def prepare_training_data(self, training_start_date):

try:

source = Path(self.state.dataset_path)

self.training_data_path = Path(f"{self.state.dataset_path}/../dataset_{training_start_date:%Y%m%d%H%M%S}")

# Bool to track if any files have been copied (if new training data is available)

files_copied = False

for split in ["train", "val"]:

for file in (source / split).rglob("*"):

if not file.is_file():

continue

# Extract timestamp from filename: image-2025-12-22T17:06:00.jpg

match = re.search(r"(\d{4}-\d{2}-\d{2}T\d{2}:\d{2}:\d{2})", file.name)

if not match:

continue

file_time = datetime.fromisoformat(match.group(1))

if file_time > self.state.last_training_timestamp:

files_copied = True

dest_path = self.training_data_path / file.relative_to(source)

dest_path.parent.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

shutil.copy2(file, dest_path)

return files_copied

except Exception as ex:

logger.exception(str(ex))

return FalseFunction prepare_training_data in model_training.py

The prepare_training_data function returns a boolean. This is used to indicate whether new training data exists. If there is no data, the function returns False and model training will not start.

When training is done, the dataset gets removed by a dedicated function.

def remove_training_data(self):

try:

shutil.rmtree(str(self.training_data_path))

except Exception as ex:

logger.exception(str(ex))Function remove_training_data in model_training.py

Scheduler for scheduled execution

It took me a moment to find a good way to implement the scheduled execution for model training. My first idea was to create background tasks using asyncio.create_task like I did for image capture and inference, but that just seemed wrong to me. Having a background task active all the time, doing nothing 90% of the time.

After some research I came across AsyncIOSchedulder, which let me create a cron-like task which runs at a specified time.

from apscheduler.schedulers.asyncio import AsyncIOScheduler

scheduler = AsyncIOScheduler()

@scheduler.scheduled_job('cron', hour=3) # Run at 3 AM daily

async def daily_training():

await asyncio.to_thread(modelTrainer.run_fine_tuning)

pass

scheduler.start()Scheduler for model training in main.py using AsyncIOScheduler

This allowed me to easily implement a schedule for model training, without having a background task running all the time.

Starting and stopping inference and image capture loops

During the implementation I ran into several issues with both overall resource usage on the Jetson and also instances where the GPU specifically was blocked by inference and image capture, causing the model training to fail.

To get around these issues I added another property in AppState to track if model training is in progress:

class AppState:

def __init__(self):

...

# Track whether training is in progress

self.training_in_progress = FalseTracking training state in AppState (state.py)

Both image capture (image_save.py) and inference (posture_monitor_inference.py) then have a check within their loop to check whether model training is in progress.

class ImageSaver():

def __init__(self, state):

...

async def run(self):

...

try:

while True:

if self.state.training_in_progress == False:Example of model training check in ImageSaver class

This means that both inference and image capture don't run while model training is running. But given that model training is running at 3 AM every night, a time where I won't be at my desk anyway, this is okay.

Model training and export to TensorRT

With all the preparation done, it was time to implement the actual model training to get the YOLO model to improve continuously.

The implementation is based on my findings comparing different approaches for model training: https://denishartl.com/yolo-11-retraining-continuous-learning/ There I found out that fine tuning while freezing the backbone layers was the best way to improve the model accuracy, so this is what I went with here. Only implementing fine-tuning also significantly reduces the dataset size, which is welcome on a very hardware restricted platform like the Jetson Orin Nano.

def train_model(self, training_start_date):

try:

model = YOLO(f"{self.state.model_path}/jetson-posture-monitor.pt")

results = model.train(

data=self.training_data_path,

epochs=15,

patience=5, # Stop if validation doesn't improve for multiple epochs

imgsz=640,

save=True,

plots=False,

lr0=0.001, # Lower learning rate for fine tuning

batch=1, # Low batch count because of low memory on Jetson

workers=1, # Low data retrieval worker count because of low memory on Jetson

freeze=10, # Freeze the backbone layers

device="cuda", # Train on GPU

name=f"finetune-{training_start_date:%Y%m%d%H%M%S}"

)

# Clean up training memory before file operations

del model

gc.collect()

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

# Move old model to backup

shutil.move(

f"{self.state.model_path}/jetson-posture-monitor.pt",

f"{self.state.model_path}/backup/jetson-posture-monitor-{training_start_date:%Y%m%d%H%M%S}.pt"

)

shutil.move(

f"{self.state.model_path}/jetson-posture-monitor.engine",

f"{self.state.model_path}/backup/jetson-posture-monitor-{training_start_date:%Y%m%d%H%M%S}.engine"

)

# Move new pytorch model to model dir

shutil.move(

f"{results.save_dir}/weights/best.pt",

f"{self.state.model_path}/jetson-posture-monitor.pt"

)

except Exception as ex:

logger.exception(ex)Function train_model in model_training.py used to fine-tune the YOLO classification model

I decided to go with 15 training epochs max, a patience of 5 epochs (stops training if validation accuracy doesn't improve for 5 consecutive epochs) and a lower learning rate of 0.001 to avoid running into over fitting over time. I don't know yet if these settings will work long-term, but these are what I am starting with. The lower learning rate hopefully will cause the model to not "forget" earlier images it learned, and improve it's capabilities over time.

Once model training is done, the old model gets moved to a backup folder and replaced with the newly trained model. It then gets exported to TensorRT format to enable significant performance improvements on Jetson. I investigated this in part 1 of the Jetson Posture monitor series and was able to get a 2x performance improvement, simply by exporting the model to TensorRT format.

def convert_model_to_tensorrt(self):

try:

# Additional cleanup before export to free up as much memory as possible

gc.collect()

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

model = YOLO(f"{self.state.model_path}/jetson-posture-monitor.pt") # load newly trained model

# Export the model

model.export(

format="engine", # Export in TensorRT format

half=True,

data=self.training_data_path,

device="cuda",

workspace=2,

batch=1

)

# Memory cleanup

del model

gc.collect()

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

except Exception as ex:

logger.exception(ex)Function convert_model_to_tensorrt in model_training.py used to export the trained model to TensorRT format

During the implementation of model training and export I ran into a bunch of issues because of the limited memory available on the Jetson. My default setup for coding was to use a VScode remote session to the Jetson. Up until this point this was fine, but the memory overhead of about ~2GB just for the VScode remote server, combined with model training and export, was too much for the Jetson to handle. So I switched to using Sublime Text with the SFTP plugin for coding.

I set these parameters for model training and export to minimize memory usage.

# Training

plots=False, # Don't save plots to save memory

batch=1, # Minimize image batch size

workers=1, # Low data retrieval worker count because of low memory on Jetson

# Export

workspace=2, # Limit export memory usage

batch=1 # Minimize image batch sizeParameter settings for model training and export to minimize memory usage

Additionally I also implemented some garbage collection and cleanup throughout the code to minimize memory usage even further.

del model

gc.collect()

torch.cuda.empty_cache()Garbage collection and cleanup throughout the app to free up memory

Conclusion

There was a lot of ground covered in this blog post. Phew! 😮💨

Starting with some general improvements to the Jetson Posture Monitor app by implementing logging and better error handling, implementing continual training data collection and a web UI for human-in-the-loop data labeling, and finally adding the continuous model training / fine tuning to the app, I learned a LOT during all of this.

Whether the continuous model improvement actually works and the model actually improves over time remains to be seen, but implementing all of this has been a very fun and interesting journey nonetheless.

All the code covered in this post can be found in my GitHub repository:

While the continuous learning loop I now implemented in the Jetson Posture Monitor app will hopefully help the model improve over time, increasing accuracy and reliability, there is still room for improvement.

Instead of continuously improving the same model over and over again, a combined approach where a model is trained from scratch once a week, and then fine-tuned throughout the week, would probably yield better results over time. Maybe I will look into this in the future.

Wrapping Up

It was a lot of work wrapping my head around all of the new-to-me concepts in this post, but it was also very fun and I learned a lot. In this part I absolutely noticed that coding entire apps isn't what I usually do, so there were many new concepts I had to get familiar with. Most notably everything around async operations, a topic where I am still not 100% confident.

Have you implemented continuous learning in your edge AI projects? Let me know your approach in the comments. ❤️

If you like what you've read, I'd really appreciate it if you share this post. 🔥

Until next time! 👋

Further reading

- Jetson Posture Monitor GitHub repository: https://github.com/denishartl/jetson-posture-monitor

- Part 1 of the Jetson Posture Monitor series (initial model training): https://denishartl.com/yolo-posture-detection-jetson-orin-nano/

- Part 2 of the Jetson Posture Monitor series (web UI and alerting): https://denishartl.com/jetson-posture-detection-fastapi-alerting/

- Sublime Text: https://www.sublimetext.com/

- YOLO training documentation: https://docs.ultralytics.com/modes/train/